As long as the question of beginnings is unanswered, we will always feel half-begun and a mystery to ourselves.

If you have a few minutes to spare, let’s spend some time together pondering the Kalam Cosmological Argument, which states: “Everything that has a beginning has a cause.”

Let me give you a moment to take that in.

From this springs the idea that the Big Bang is not the beginning of the universe, just the current boundary of our rearward knowledge.

As we have been taught, the Big Bang marked the release of an inconceivable amount of pure energy, enough to form the now-still-expanding universe, not just its materiality (billions of galaxies, each with billions of stars, many with orbiting space junk like our planet), but also void space itself, whose immensity cannot be held by thought.

It’s fascinating and mind-boggling to ask: What was that inconceivable amount of pure energy doing the day before the Big Bang? After all, assuming the Big Bang was a temporal event, the clock must have been ticking earlier.

What was it? Where was it? Remember: As far as we know, something doesn’t come from nothing.

Pre-Bang, how much room did the universe occupy? I don’t say “how much space” because it appears the Big Bang itself created space. And if there wasn’t any space before the Big Bang, what did the Big Bang expand into? Not-space?

Did the energy occupy one cubic foot? More? Less? Does it compress and un-become itself? And if yes, then how does that work?

Again: “Everything that has a beginning has a cause.”

Confronted by this puzzle, you eagerly reach for a kind of convenient logic and say: “Well, there was a universe before this one and in some cosmic cycle, that universe expanded, then contracted, with all matter and energy rushing toward a particular point, and eventually compressing so much that it triggered another Big Bang, and here we are in that next and current universe.”

Clever you! You realize that this doesn’t actually answer the question of causation. It simply postulates an infinite regression of Big Bangs without identifying a cause, and tries to postpone the puzzle, the mystery, of creation.

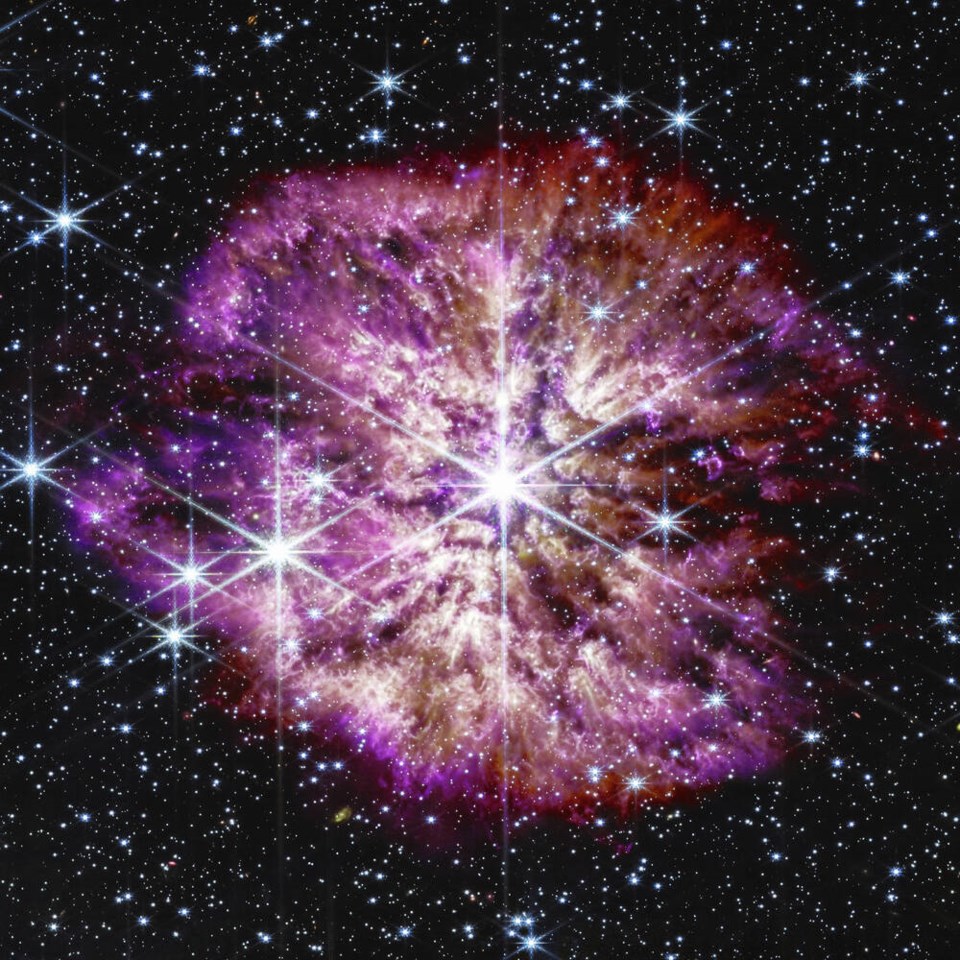

Quite recently, the James Webb telescope has picked up energetic emanations, some otherwise inexplicable signature, that suggest the presence of one or more parallel universes, setting off Big Bangs as they collide or rub up against each other (this is hard stuff to language).

And before the first of these?

Other people say: “God” or, more revealingly, “an uncaused Creator.” Can’t tussle with that — either you like Cheezies or you don’t.

The Kalam Cosmological Argument is a contemporary reformulation of a medieval Islamic proposition intended to prove the existence of God — an effort to quench the thirst for knowledge of beginnings.

And there rests the ever-readjusting three-sided balance between religious mystery, scientific discovery and …uh … video games.

Religious faith exists because our existential compasses don’t point true north, and because there’s a hole in our intellectual imaginations — our “souls” — a plaguing lacuna in our knowledge of our origins.

I can put this colloquially: “If you don’t know where you’ve come from, you don’t know where you’re heading.”

This just might provide an explanation for the importance that “How?” and “Why?” occupy in our lexicon.

Whatever energy produced the universe, we are not “other” but “of” it.

Something far beyond biological explanation makes that so. Whatever that energy was and is, we have kinship with its essence, since we’re one of its cosmic expressions. In the strongest sense, it’s our identity, our heritage.

You’ve probably noticed that there’s a half-finished, work-in-progress quality to human projects. Well, if there’s no closure in the universe, why hope for closure here?

Maybe all of this points to a new touristic future for Victoria, since the “Little Olde” thing has collapsed under the weight of highrises: “World Capital of Half-finished Projects.”

As long as the question of beginnings is unanswered, we will always feel half-begun and a mystery to ourselves.

Maybe, if we knew absolute beginnings, the frantic search would cease and we could settle down and play nice.

Possibly, the discovery of beginnings would let us make peace with ends.

[email protected]

Gene Miller is the founder of Open Space, founding publisher of Monday Magazine, originator of the Gaining Ground urban sustainability conferences, founder/developer of ASH houseplexes, and currently writing “Nothing To Do: Life in a Post-Work World.” He’d be pleased to receive and respond to your thoughts.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor:[email protected]