Injured claimants who exhaust ICBC’s process and lose at the civil resolution tribunal go to court without lawyer or legal expertise.

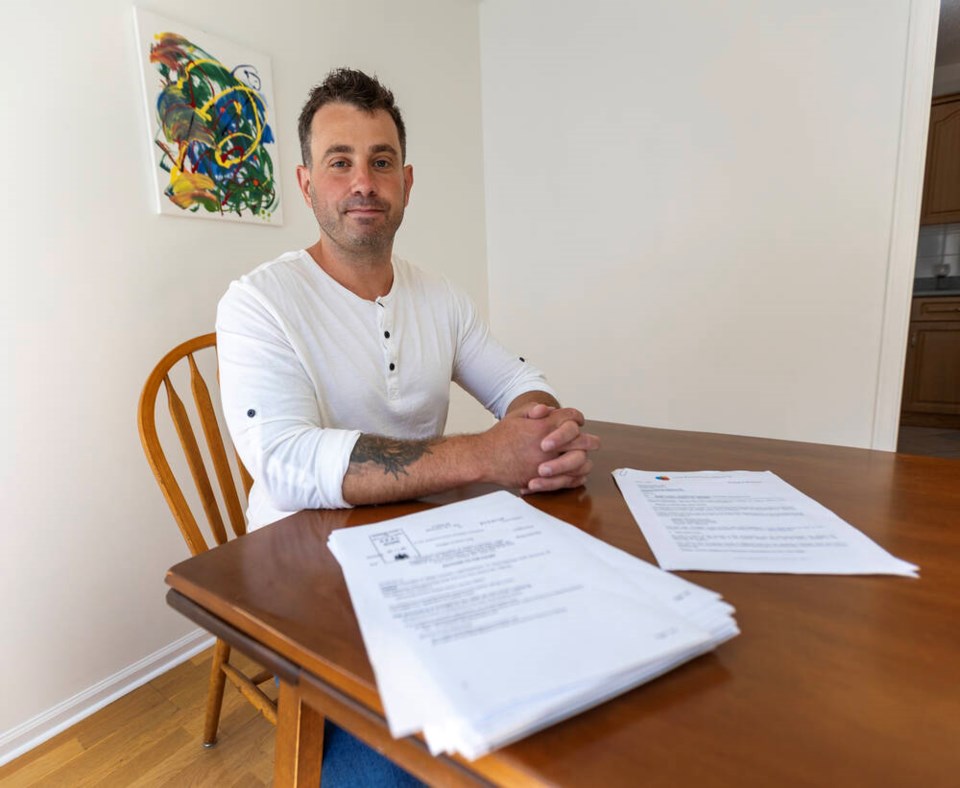

Almost three years ago, Reagan Kucher-Lang was hit by a car while riding his bike near the Victoria waterfront. He flew over the hood of the vehicle and hit the pavement. He was later diagnosed with post-concussion syndrome.

Kucher-Lang sought compensation, first from ICBC and then from B.C.’s civil resolution tribunal, for the loss of past and future wages and compensation for a permanent injury.

He was denied both times.

So he is taking his case to B.C. Supreme Court.

“This whole thing has been a nightmare. It’s taken over my life and it’s still taking over my life,” said Kucher-Lang, a 35-year-old insurance broker. “They declined my claim straight off the bat. … I still have a brain injury.”

Kucher-Lang’s case is one of several winding their way through the courts under the province’s no-fault insurance system.

The province adopted the system, which it calls “enhanced care,” in 2021, ending the right of injured crash victims to sue an at-fault driver.

Since then, ICBC has handled 296,500 claims for accident benefits. As of late June, 568 claimants — or 0.19 per cent — had challenged ICBC’s decisions through the civil resolution tribunal.

Kucher-Lang is one of three people who have filed for a judicial review after their claims were denied by that tribunal. All three were filed within the past six weeks.

A recent review by UBC’s Allard School of Law raised questions about the fairness of the tribunal process. Researchers determined ICBC was the winner in 91 per cent of tribunal cases it heard between 2021 and the end of 2023, when there were 32 decisions.

“Strong indications of pervasive power imbalances exist” between the injured and ICBC, concluded Kaitlyn Cumming, an Allard PhD student whose study appeared in the Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice, a peer-reviewed journal.

ICBC’s figures from 2021 to the end of June 2025 show the tribunal heard 122 cases. ICBC won 67 of those cases or 55 per cent, while claimants won nine cases or seven per cent.

In 36 cases, the tribunal’s decision was a mixed outcome and it dismissed 10 cases. An additional 114 cases were withdrawn. More than 300 cases filed with the tribunal are “still active,” says ICBC.

Cumming’s research shows claimants who challenge ICBC decisions at the civil resolution tribunal usually do so without a lawyer because of prohibitive legal fees, and they struggle with gathering or presenting simple evidence.

The report noted recurring examples where adjudicators dismissed claims because claimants failed to present receipts for medical treatments or medications, a doctor’s report, or financial documents such as pay stubs or human resources records.

ICBC reviews tribunal rulings to “ensure claim outcomes are consistent and fair,” ICBC spokesman Greg Harper said in an email, and uses decisions to “help us identify where policies can be improved because enhanced care is still evolving and [tribunal] insights are essential to shaping its future.”

Cumming’s report recommends that the government subsidize legal help for claimants to improve access to justice.

For self-represented claimants who challenge civil resolution tribunal decisions in the courts, the odds of success are even smaller because it’s a “big step up in complexity,” with much stricter requirements than the tribunal’s processes, Cumming said in an email.

“It is challenging for self-represented litigants to navigate the court system of appeal and judicial review,” agreed Sam Beswick, a professor at the UBC law school. “It’s a complex practice that presupposes legal training and skill.”

ICBC confirmed there are three petitions before the B.C. Supreme Court for judicial reviews of tribunal decisions on accident-benefit claims and that all three claimants appear to have filed without a lawyer.

ICBC lawyers have filed responses to the three petitions, opposing them. Hearing dates have yet to be set.

“The [tribunal] is designed to be easy to use for non-lawyers, but claimants have to go up against ICBC employees whose only job is to defend claims and, by default, they’re at a disadvantage,” said Greg Phillips of the Trial Lawyers of Association of B.C., which opposes the no-fault system.

The judicial review process in B.C. Supreme Court is “highly technical” and is not like going before a regular appeals court, where a judge can allow the appeal and may substitute a new award, Phillips said.

In Supreme Court, a judge has to determine whether the adjudicator made a serious error of law or showed a lack of procedural fairness, unreasonableness or patent unreasonableness, meaning the decision was “so obviously wrong that the court has no choice but to intervene,” he said.

Even if a claimant is successful at having a tribunal decision overturned by a judge, the case would likely be returned to the tribunal to be reheard with no guarantee of success the second time, said Phillips and Cumming.

The outcomes of the first judicial reviews will be important because the precedents will stand for others that follow, said Phillips.

Before deciding to take his case to the tribunal and then B.C. Supreme Court, Kucher-Lang said he exhausted the appeal process within ICBC, which he described as “broken.”

“They just redirected me to another ICBC manager,” he said.

Kucher-Lang’s case was complicated by the fact he worked for months while concussed because he wasn’t properly diagnosed until months after his November 2022 accident.

He said he was injured again five months later, in April 2023, when three drunken university students pushed him off a city bus and assaulted him. He was treated for several injuries in an emergency department and filed a police report, but no one was charged.

Two months later, he returned to hospital with stomach pain and was referred to an internist who diagnosed him with “extensive post-concussion symptoms” for the first time in August 2023.

Kucher-Lang said the doctor said it was “ridiculous” that he had worked after the crash and sent him to a new family doctor, who confirmed the diagnosis and referred him to a neurologist, who also confirmed the diagnosis.

His continuing symptoms, including headaches, brain fog and fatigue, prevented him from working after he was let go during a restructuring six months after the crash.

ICBC did not accept that his injury was caused by the crash, so he appealed to the tribunal. Kucher-Lang submitted doctor reports and proof of his provincial and federal disability designations for tax purposes and disability payments.

ICBC maintained his post-concussion syndrome was likely the result of the assault on the bus and that he hadn’t proved he was entitled to income replacement, permanent injury compensation or health benefits beyond the eight physiotherapy sessions in 2023 that it had already funded.

Kucher-Lang did get a partial victory. The tribunal adjudicator found his post-concussion syndrome was caused by the car crash, and ordered ICBC to reimburse Kucher-Lang for medication expenses when he provided proper receipts.

But the adjudicator denied Kucher-Lang’s claim for compensation for lost wages and for permanent injury because he said a doctor believed he would improve with medication and treatment, and noted he was on a waiting list for a concussion rehab clinic.

For his Supreme Court appeal application, Kucher-Lang tracked down ICBC precedents online and used a legal artificial intelligence app that suggested his case was winnable. He filed his petition for review in May and is now waiting for the court hearing.

Kucher-Lang, who has now returned to work part-time as a broker, is representing himself after receiving a $20,000 quote from a lawyer. The lawyer did offer him some free help.

ICBC defends the no-fault system, noting that injured people are eligible for medical treatment and wage replacement whether at fault or not, medical treatments such as physiotherapy are available for three months without a doctor’s referral, and income-replacement benefits are based on 90 per cent of take-home pay rather than a set weekly limit.

But Cumming concludes in her paper there needs to be a “culture change packaged as part of the reforms” for no-fault to be successful.

To improve access to justice, more research is needed to determine why ICBC is disproportionately successful in civil resolution tribunal decisions, Cumming wrote in her report.

The fact there have been only three requests for judicial reviews over four years might indicate that without a lawyer, many claimants may not even recognize that tribunal adjudicators, or ICBC case managers before them, had made a judicially reviewable error, she said in an email.

Also unknown, says Cumming in her report, is how the system can improve access to justice for claimants who don’t have lawyers and are suffering from more complex medical issues such as lingering concussions or chronic pain, as the medical field continues to learn more about those conditions.

She recommends that government fund legal aid for civil cases or subsidize legal services to “help equalize and redistribute legal capital” between parties.

Cumming also recommends that lawyers provide unbundled legal services for specific tasks to help claimants prepare a submission to the civil resolution tribunal or to provide guidance.

Phillips said any ICBC case is time-consuming and costly to take on, and any legal help would likely have to come from articling or law students and not experienced lawyers.

Garry Begg, B.C.’s solicitor general, who oversees ICBC, didn’t respond to emailed questions about the recommendations, but a ministry spokeswoman said in an email that it continues to monitor and evaluate the no-fault system and the civil resolution tribunal.

After ICBC filed a response to his petition, Kucher-Lang received a letter from a downtown Vancouver law firm representing ICBC. It recommended he hire a lawyer for the judicial review.

“It’s the most ludicrous thing” because his injury is both the reason he needs a lawyer and the reason he can’t afford one, he said. “It’s definitely David versus Goliath.”

And he feels like he had to become “basically a makeshift lawyer,” spending “months and months and months” researching the law before the application, for which he had to learn how to use the courthouse computers in order to proceed.

It has cost him time and money to make four copies of a 430-page evidence booklet, serve ICBC and the civil resolution tribunal the petition, and prepare to go before a judge — all while he suffers the effects of a head injury.

But he remains determined to have his case heard in court.

“I believe ICBC is manipulating and abusing their power. They’re taking away the benefits of seriously injured people. It’s not enhanced care.”

Read more stories from the Vancouver Sun here.